Hide in your shell

A curious study on building retrofit emissions... and foam

Hi Folks,

I’ve been a little bit on the back foot since the operation, which I put down to having breathed f-gases for a few hours... you can catch up on my (partial) recollection here if you missed it.

At the same time, there continues to be a raft of papers and reports being generated in the climate space. Including refrigerants and f-gases. The stack waiting to be read gradually rising. There was one that caught my eye recently, just because it touched on an area that doesn’t get much attention.

That of refrigerant emissions from building insulating foams.

If you thought refrigerant emissions was aleady niche in the climate conversation, foams takes you into even nicher territory.

The core finding of the paper was this. In building retrofits, dealing with the emissions from the insulating foams could have a greater lifecyle impact than that of the reduced energy use. I dug in.

Sensitivity

The paper I’m referring to was titled ‘Sustainable Retrofit of Existing Buildings: Impact Assessment of Residual Fluorocarbons through Uncertainty and Sensitivity Analyses’.

To be honest, given the pile of papers waiting to be read, this one sounded like hard work. Like many academic papers, in contains plenty of formulas, graphs and some hefty mathematical discussions.

There were however some genuinely interesting ideas; ones I hadn’t seen explored in other studies.

While folks are now starting to tune in to the challenges of fluorinated refrigerants in air-conditoning and heat pumps, the presence of refrigerant gases in the foams is less well known. I touched on this in one of my earlier editions, discussing the other sources of f-gas emisions in buildings.

For a quick recap, refrigerant gases (CFCs/HFCs/HFOs) are used to expand the foam during manufacturing. That is to create the bubbles, and their use described as ‘blowing agents’. Some of these foams are then applied as building insulation.

Most of the gases are trapped in the foam, however they do gradually leak out over time. And they present a real climate (and ozone) risk when the building is demolished or renovated (i.e. discarded on the scrap pile).

Digging into the paper, it looked at scenarios for renovating a typical older, multi-story residential building, currently fitted with insulation containing refrigerants.

It posed the question, as to what would happen if you replaced the existing f-gas containing insulating foams completely, or just wrap a thinner layer around the outside. In both cases the objective being to improve the thermal performance and to reduce energy use.

While I was aware that foams have an annual leak rate (0.25-2.5% annually was used in the study), what I hadn’t seen described before was the total lifecycle emissions from all the insulation foam on a building, then compared to the building energy emissions. The results were surprising.

Just adding a thinner, outer insulating layer (but keeping in place the older existing f-gas foams) would improve the energy performance, but allow the f-gas emissions to continue for the life of the building.

However, removing the old insulation (specifically those containing CFCs, common for construction pre-90s), and replacing it with modern, non-fluroinated insulation would provide twice the lifecycle emissions benefit of the reduced energy use from the retrofit.

To quote from the study.

“As a result, the removal and correct disposal of CFC/HFC banks (in insulating foams) can constitute, where technically feasible, significant environmental impact savings, even higher than that obtainable from energy retrofit measures”

This loops back to another point regarding CFCs (the ozone depleting gases). People often think that the problem has been solved. The reality is that while production for many uses is phased out, they are still being held captive in lots of foams. For example in refrigerators and also fixed to the walls of buildings.

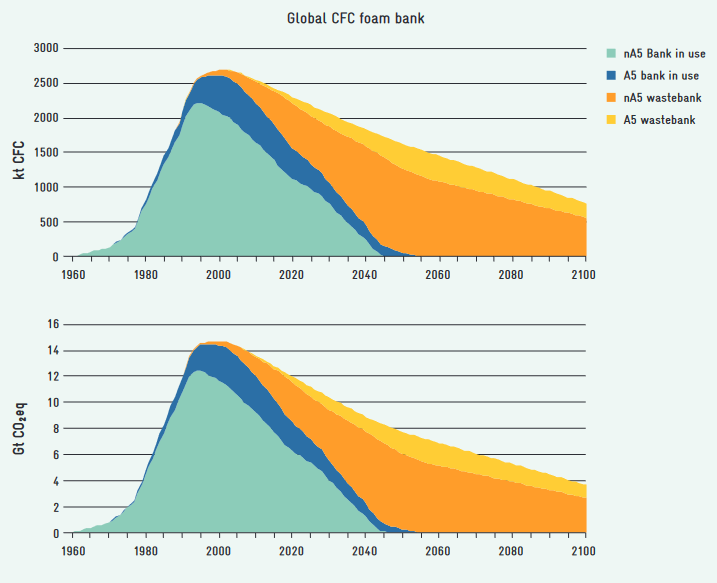

The graph below provides an idea of the scale.

For some reference. Even as these are banked, our total global annual GHG emissions are circa 50 Gt. So while there is increasing attention being paid to refrigerants used in heating and cooling, we musn’t overlook the other sources either.

One other point raised in the paper that I hadn’t given much thought to either. What happens when the building is in an area of seismic activity? Even with mild shocks, it can affect the integrity of the insulation foam and release the f-gases inside. There is another related paper exploring that topic further. That is even more niche…

Right, enough for this week and ‘till next time,

Adrian.

If you’d like to dive deeper you can find the study here:

Maracchini, G.; Di Filippo, R.; Albatici, R.; Bursi, O.S.; Di Maggio, R. Sustainable Retrofit of Existing Buildings: Impact Assessment of Residual Fluorocarbons through Uncertainty and Sensitivity Analyses. Energies 2023, 16, 3276. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16073276

p.s. the title track from the last edition – Now they’ll sleep -was from the great album, King, by Belly

p.p.s. While I get myself back up to speed, I’m going to take a pause for the coming week, normal service to resume shortly

Fixed stuff here for newcomers

There is lots of news every week from the cooling industry and plenty of newsletters that cover it well. The intention is to keep this newsletter focused on the most prominent f-gases (fluorinated greenhouse gases), the most common of which are refrigerants and importantly their environmental impact. That’s the lane I’ve chosen - I’ll do my best to stick to it.

The What

Below are the seven formal greenhouse gases that countries and companies should track, report and hopefully reduce.

Carbon Dioxide (CO2)

Methane (CH4)

Nitrous Oxide (N2O)

Hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs)

Perfluorocarbons (PFCs)

Sulphur Hexafluoride (SF6)

Nitrogen trifluoride (NF3)

Plus the still circulating, ozone damaging chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs), and the ‘new-generation’ hydrofluoroolefins (HFOs).

Hopefully you can spot the pattern.

The Why

Emissions from f-gases and refrigerants have been the fastest growing greenhouse gases over the past decade (more than CO2 and methane - check out IPCC WG3 summary for policy makers). They are also classed as super pollutants given their outsized global warming and other environmental impacts.

You can find my basic primer here and a plenty more detail in the whitepaper here

Some useful permalinks

The scale of the climate challenge can often feel daunting. This piece helps me take a step back and understand where we need to focus first - recommend a read.

There are plenty of technology solutions available to address the cooling and refrigerant challenge. You can find many of them here

Beware when the same entities who have contributed to the current f-gas problem propose you new solutions… This is a good place to get up to speed.