Hi Folks,

In the last edition, I attempted to distill the problem I’m dedicated to working on. The climate and broader environmental issues, connected with refrigerants.

Looking back at it, I’m not sure I succeeded completely. There are the main technical points covered, but maybe I needed something visual to get the idea across.

I think I used just shy a thousand words in trying, and you know what they say about pictures and their worth.

So let me try a different approach. Using a…

Bathtub

The bathtub analogy is often used to describe the problem with the build-up of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. It is cumulative, meaning it is the total ‘stock’ of CO2 that is the problem. I remember sitting in a seminar over a decade ago when I first heard the analogy described. It was a real lightbulb moment for me.

Even if we close off the human-generated CO2 taps tomorrow, there is still a bathtub full that will continue to deliver warming for some time. The rate at which CO2 currently ‘drains away’ naturally is also slower than what is being added, hence why it continues to fill. There is a further explainer on it here.

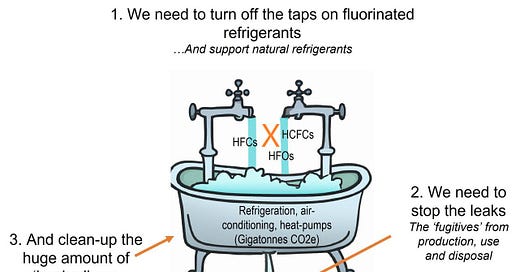

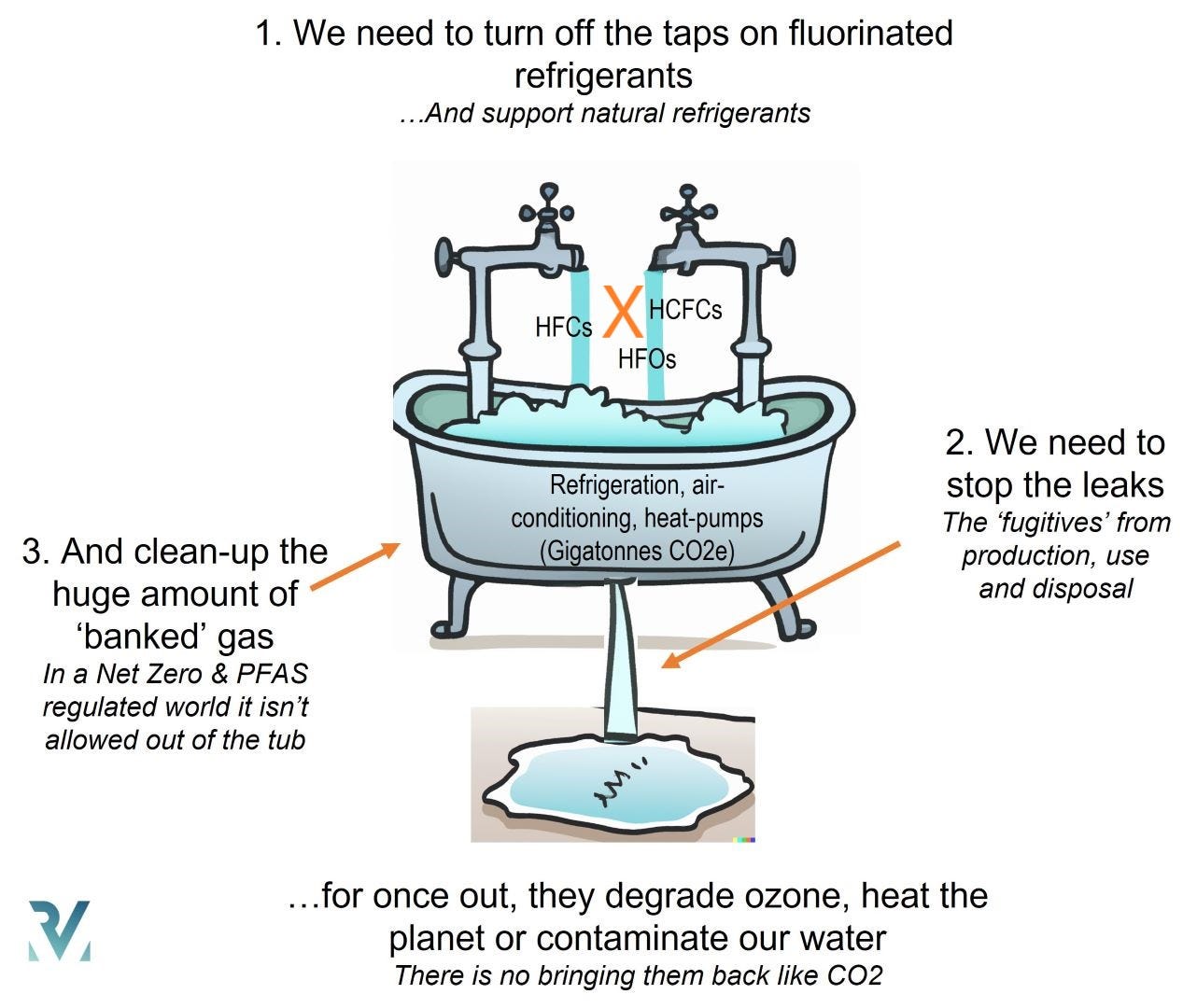

I think we can utilise some of this analogy to describe the problems with using fluorinated refrigerants and the required actions, albeit with a few differences. We’ll also put aside the other f-gases and applications for the moment to keep it simple.

With CO2 we are talking about what is already in the atmosphere, some of which is naturally occurring and necessary (the excess being the problem). In my diagram on refrigerants however, I’m referring to gases produced in chemical plants, contained in man-made equipment (air-conditioners and heat pumps for example), and put to work all around us down here. These are the ‘BigF’ gases I referred to last week.

As it stands today, there are inflows of BigF chemicals, via their manufacture and use. There are also outflows primarily from leaks (fugitives) and destruction. The outflows via leaks are throughout their entire lifecycle from cradle to grave. And all refrigerant containing systems leak, some tiny amounts, and some a great deal.

These fugitive outflows are hugely problematic as we’ve discussed last week. And as many BigF gases have atmospheric lifetimes measured in decades, their climate impact is in the near term. Important when you are trying to make steep reductions.

As we work towards our global net zero goals, and include PFAS restrictions, these ‘fugitive’ emissions will need to be plugged at every step. There are some programs and efforts to address these but far more needs to be done.

At the same time, we also need to be reducing the quantity of BigF refrigerants entering the tub. There are mechanisms to drive this such as the Kigali amendment and US AIM act. Currently these apply to HFC refrigerants but allow use of other fluorinated chemicals.

That’s why you’ll hear me talking about topics like HFOs and PFAS. The need to turn down the taps on those refrigerants and turn up the taps on alternatives. Leak mitigation is still vital and data tools and proactive monitoring can make a big impact. Plus, the ongoing clean-up operation to address the tub-full of refrigerants already in circulation. I’m working within COPA to help tackle that one also.

While there are of course details missing in using a simple analogy, it helps direct my focus and hopefully helps some others.

I’ll leave it there for today but let me know what you think. Whether this helps and what needs more clarity? It’s a work in progress…

Where the F-has hides

Each week I provide an example of where f-gases are utilised, or used to produce something. They are present in more things than most people realise… #wherethefgashides

I normally work from home a couple days a week. On those days I normally get a gentle nudge to put on a load of washing, especially if there is a hint of sun or breeze.

So it leads me to this week’s f-gas hiding place. Clothes dryers. And more specifically heat pump clothes dryers (HPCDs also known as HP tumble dryers)

HPCDs

For a quick introduction to those unfamiliar, HPCDs use heat-pump (or reverse air-conditioning) technology to remove moisture from clothes. Traditionally this has been done with electric heating or gas combustion. However through the magic of refrigerants, heat-pumps can do the same job with energy savings ranging from 25-50% (some report even higher depending on what you’re comparing to).

Terrific you might think. And for reducing electricity or fossil gas use they are genuinely helpful. However many of these heat-pumps also use refrigerants with a global warming potential over a thousand times higher than CO2. For example R134a is a common refrigerant used in these appliances.

While the refrigerant is contained in the clothes dryer, all is fine. However we know that many appliances are dumped unceremoniously at the end of their working life. Many folks are also unaware that their dryer contains these climate damaging gases, which means they may not get handled appropriately. They should be handled in the same way as refrigerators.

Quick example. If all the refrigerant was ‘accidentally’ released at disposal it would be roughly the same impact as the energy emissions from running the HPCD for 10 years (based on one wash per week). You could undo all your well-meaning efficiency efforts very quickly.

As HPCDs are ‘relatively’ new to the market you can see this problem getting bigger over time as more enter the waste stream. And like the other appliances we discussed last week, natural refrigerants can also be used. Perhaps the HPCD appliance makers need a push in the same way as the GreenFreeze program.

Of course you can revert back to those other renewable sources for drying clothes. Wind and sun.

Right, that’s all for this week and ‘till next time

Adrian

p.s. the title track from last week – You make it easy – was from the album Moon Safari, by Air. An album I’ve often pulled out to calm the nerves before a big event…

Fixed stuff here for newcomers

There is lots of news every week from the cooling industry and plenty of newsletters that cover it well. The intention is to keep this newsletter focused on the most prominent f-gases (fluorinated greenhouse gases), the most common of which are refrigerants and importantly their environmental impact. That’s the lane I’ve chosen - I’ll do my best to stick to it.

The What

Below is the seven (formal) greenhouse gases that countries and companies should track, report and hopefully reduce.

Carbon Dioxide (CO2)

Methane (CH4)

Nitrous Oxide (N2O)

Hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs)

Perfluorocarbons (PFCs)

Sulphur Hexafluoride (SF6)

Nitrogen trifluoride (NF3)

There is also the still circulating, ozone damaging chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs), and the ‘new-generation’ hydrofluoroolefins (HFOs).

Hopefully you can spot the pattern.

The Why

Emissions from f-gases and refrigerants have been the fastest growing greenhouse gases over the past decade (more than CO2 and methane - check out IPCC WG3 summary for policy makers). They are also classed as super pollutants given their outsized global warming and other environmental impacts.

You can find my basic primer here and a plenty more detail in the whitepaper here

Some useful permalinks

The scale of the climate challenge can often feel daunting. This piece helps me take a step back and understand where we need to focus first - recommend a read.

There are plenty of technology solutions available to address the cooling and refrigerant challenge. You can find many of them here

Beware when the same entities who have contributed to the current f-gas problem propose you new solutions… This is a good place to get up to speed.